You are here

April 23, 2024

Research in Context: Treating depression

Finding better approaches

While effective treatments for major depression are available, there is still room for improvement. This special Research in Context feature explores the development of more effective ways to treat depression, including personalized treatment approaches and both old and new drugs.

Everyone has a bad day sometimes. People experience various types of stress in the course of everyday life. These stressors can cause sadness, anxiety, hopelessness, frustration, or guilt. You may not enjoy the activities you usually do. These feelings tend to be only temporary. Once circumstances change, and the source of stress goes away, your mood usually improves. But sometimes, these feelings don’t go away. When these feelings stick around for at least two weeks and interfere with your daily activities, it’s called major depression, or clinical depression.

In 2021, 8.3% of U.S. adults experienced major depression. That’s about 21 million people. Among adolescents, the prevalence was much greater—more than 20%. Major depression can bring decreased energy, difficulty thinking straight, sleep problems, loss of appetite, and even physical pain. People with major depression may become unable to meet their responsibilities at work or home. Depression can also lead people to use alcohol or drugs or engage in high-risk activities. In the most extreme cases, depression can drive people to self-harm or even suicide.

The good news is that effective treatments are available. But current treatments have limitations. That’s why NIH-funded researchers have been working to develop more effective ways to treat depression. These include finding ways to predict whether certain treatments will help a given patient. They're also trying to develop more effective drugs or, in some cases, find new uses for existing drugs.

Finding the right treatments

The most common treatments for depression include psychotherapy, medications, or a combination. Mild depression may be treated with psychotherapy. Moderate to severe depression often requires the addition of medication.

Several types of psychotherapy have been shown to help relieve depression symptoms. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy helps people to recognize harmful ways of thinking and teaches them how to change these. Some researchers are working to develop new therapies to enhance people’s positive emotions. But good psychotherapy can be hard to access due to the cost, scheduling difficulties, or lack of available providers. The recent growth of telehealth services for mental health has improved access in some cases.

There are many antidepressant drugs on the market. Different drugs will work best on different patients. But it can be challenging to predict which drugs will work for a given patient. And it can take anywhere from 6 to 12 weeks to know whether a drug is working. Finding an effective drug can involve a long period of trial and error, with no guarantee of results.

If depression doesn’t improve with psychotherapy or medications, brain stimulation therapies could be used. Electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, uses electrodes to send electric current into the brain. A newer technique, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), stimulates the brain using magnetic fields. These treatments must be administered by specially trained health professionals.

“A lot of patients, they kind of muddle along, treatment after treatment, with little idea whether something’s going to work,” says psychiatric researcher Dr. Amit Etkin.

One reason it’s difficult to know which antidepressant medications will work is that there are likely different biological mechanisms that can cause depression. Two people with similar symptoms may both be diagnosed with depression, but the causes of their symptoms could be different. As NIH depression researcher Dr. Carlos Zarate explains, “we believe that there’s not one depression, but hundreds of depressions.”

Depression may be due to many factors. Genetics can put certain people at risk for depression. Stressful situations, physical health conditions, and medications may contribute. And depression can also be part of a more complicated mental disorder, such as bipolar disorder. All of these can affect which treatment would be best to use.

Etkin has been developing methods to distinguish patients with different types of depression based on measurable biological features, or biomarkers. The idea is that different types of patients would respond differently to various treatments. Etkin calls this approach “precision psychiatry.”

One such type of biomarker is electrical activity in the brain. A technique called electroencephalography, or EEG, measures electrical activity using electrodes placed on the scalp. When Etkin was at Stanford University, he led a research team that developed a machine-learning algorithm to predict treatment response based on EEG signals. The team applied the algorithm to data from a clinical trial of the antidepressant sertraline (Zoloft) involving more than 300 people.

EEG data for the participants were collected at the outset. Participants were then randomly assigned to take either sertraline or an inactive placebo for eight weeks. The team found a specific set of signals that predicted the participants’ responses to sertraline. The same neural “signature” also predicted which patients with depression responded to medication in a separate group.

Etkin’s team also examined this neural signature in a set of patients who were treated with TMS and psychotherapy. People who were predicted to respond less to sertraline had a greater response to the TMS/psychotherapy combination.

Etkin continues to develop methods for personalized depression treatment through his company, Alto Neuroscience. He notes that EEG has the advantage of being low-cost and accessible; data can even be collected in a patient’s home. That’s important for being able to get personalized treatments to the large number of people they could help. He’s also working on developing antidepressant drugs targeted to specific EEG profiles. Candidate drugs are in clinical trials now.

“It’s not like a pie-in-the-sky future thing, 20–30 years from now,” Etkin explains. “This is something that could be in people’s hands within the next five years.”

New tricks for old drugs

While some researchers focus on matching patients with their optimal treatments, others aim to find treatments that can work for many different patients. It turns out that some drugs we’ve known about for decades might be very effective antidepressants, but we didn’t recognize their antidepressant properties until recently.

One such drug is ketamine. Ketamine has been used as an anesthetic for more than 50 years. Around the turn of this century, researchers started to discover its potential as an antidepressant. Zarate and others have found that, unlike traditional antidepressants that can take weeks to take effect, ketamine can improve depression in as little as one day. And a single dose can have an effect for a week or more. In 2019, the FDA approved a form of ketamine for treating depression that is resistant to other treatments.

But ketamine has drawbacks of its own. It’s a dissociative drug, meaning that it can make people feel disconnected from their body and environment. It also has the potential for addiction and misuse. For these reasons, it’s a controlled substance and can only be administered in a doctor’s office or clinic.

Another class of drugs being studied as possible antidepressants are psychedelics. These include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. These drugs can temporarily alter a person’s mood, thoughts, and perceptions of reality. Some have historically been used for religious rituals, but they are also used recreationally.

In clinical studies, psychedelics are typically administered in combination with psychotherapy. This includes several preparatory sessions with a therapist in the weeks before getting the drug, and several sessions in the weeks following to help people process their experiences. The drugs are administered in a controlled setting.

Dr. Stephen Ross, co-director of the New York University Langone Health Center for Psychedelic Medicine, describes a typical session: “It takes place in a living room-like setting. The person is prepared, and they state their intention. They take the drug, they lie supine, they put on eye shades and preselected music, and two therapists monitor them.” Sessions last for as long as the acute effects of the drug last, which is typically several hours. This is a healthcare-intensive intervention given the time and personnel needed.

In 2016, Ross led a clinical trial examining whether psilocybin-assisted therapy could reduce depression and anxiety in people with cancer. According to Ross, as many as 40% of people with cancer have clinically significant anxiety and depression. The study showed that a single psilocybin session led to substantial reductions in anxiety and depression compared with a placebo. These reductions were evident as soon as one day after psilocybin administration. Six months later, 60-80% of participants still had reduced depression and anxiety.

Psychedelic drugs frequently trigger mystical experiences in the people who take them. “People can feel a sense…that their consciousness is part of a greater consciousness or that all energy is one,” Ross explains. “People can have an experience that for them feels more ‘real’ than regular reality. They can feel transported to a different dimension of reality.”

About three out of four participants in Ross’s study said it was among the most meaningful experiences of their lives. And the degree of mystical experience correlated with the drug’s therapeutic effect. A long-term follow-up study found that the effects of the treatment continued more than four years later.

If these results seem too good to be true, Ross is quick to point out that it was a small study, with only 29 participants, although similar studies from other groups have yielded similar results. Psychedelics haven’t yet been shown to be effective in a large, controlled clinical trial. Ross is now conducting a trial with 200 people to see if the results of his earlier study pan out in this larger group. For now, though, psychedelics remain experimental drugs—approved for testing, but not for routine medical use.

Unlike ketamine, psychedelics aren’t considered addictive. But they, too, carry risks, which certain conditions may increase. Psychedelics can cause cardiovascular complications. They can cause psychosis in people who are predisposed to it. In uncontrolled settings, they have the risk of causing anxiety, confusion, and paranoia—a so-called “bad trip”—that can lead the person taking the drug to harm themself or others. This is why psychedelic-assisted therapy takes place in such tightly controlled settings. That increases the cost and complexity of the therapy, which may prevent many people from having access to it.

Better, safer drugs

Despite the promise of ketamine or psychedelics, their drawbacks have led some researchers to look for drugs that work like them but with fewer side effects.

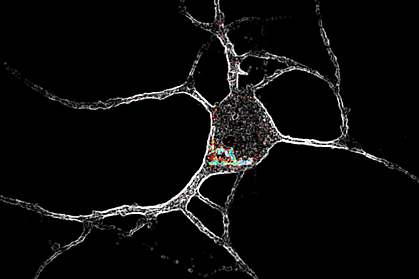

Depression is thought to be caused by the loss of connections between nerve cells, or neurons, in certain regions of the brain. Ketamine and psychedelics both promote the brain’s ability to repair these connections, a quality called plasticity. If we could understand how these drugs encourage plasticity, we might be able to design drugs that can do so without the side effects.

Dr. David Olson at the University of California, Davis studies how psychedelics work at the cellular and molecular levels. The drugs appear to promote plasticity by binding to a receptor in cells called the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor (5-HT2AR). But many other compounds also bind 5-HT2AR without promoting plasticity. In a recent NIH-funded study, Olson showed that 5-HT2AR can be found both inside and on the surface of the cell. Only compounds that bound to the receptor inside the cells promoted plasticity. This suggests that a drug has to be able to get into the cell to promote plasticity.

Moreover, not all drugs that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Olson’s team has developed a molecular sensor, called psychLight, that can identify which compounds that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Using psychLight, they identified compounds that are not psychedelic but still have rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects in animal models. He’s founded a company, Delix Therapeutics, to further develop drugs that promote plasticity.

Meanwhile, Zarate and his colleagues have been investigating a compound related to ketamine called hydroxynorketamine (HNK). Ketamine is converted to HNK in the body, and this process appears to be required for ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Administering HNK directly produced antidepressant-like effects in mice. At the same time, it did not cause the dissociative side effects and addiction caused by ketamine. Zarate’s team has already completed phase I trials of HNK in people showing that it’s safe. Phase II trials to find out whether it’s effective are scheduled to begin soon.

“What [ketamine and psychedelics] are doing for the field is they’re helping us realize that it is possible to move toward a repair model versus a symptom mitigation model,” Olson says. Unlike existing antidepressants, which just relieve the symptoms of depression, these drugs appear to fix the underlying causes. That’s likely why they work faster and produce longer-lasting effects. This research is bringing us closer to having safer antidepressants that only need to be taken once in a while, instead of every day.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

Related Links

- How Psychedelic Drugs May Help with Depression

- Biosensor Advances Drug Discovery

- Neural Signature Predicts Antidepressant Response

- How Ketamine Relieves Symptoms of Depression

- Protein Structure Reveals How LSD Affects the Brain

- Predicting The Usefulness of Antidepressants

- Depression Screening and Treatment in Adults

- Serotonin Transporter Structure Revealed

- Placebo Effect in Depression Treatment

- When Sadness Lingers: Understanding and Treating Depression

- Depression

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs

References: An electroencephalographic signature predicts antidepressant response in major depression. Wu W, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Lucas MV, Fonzo GA, Rolle CE, Cooper C, Chin-Fatt C, Krepel N, Cornelssen CA, Wright R, Toll RT, Trivedi HM, Monuszko K, Caudle TL, Sarhadi K, Jha MK, Trombello JM, Deckersbach T, Adams P, McGrath PJ, Weissman MM, Fava M, Pizzagalli DA, Arns M, Trivedi MH, Etkin A. Nat Biotechnol. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0397-3. Epub 2020 Feb 10. PMID: 32042166.

Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, Schmidt BL. J Psychopharmacol. 2016 Dec;30(12):1165-1180. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512. PMID: 27909164.

Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponté KL, Guss J, Bossis AP, Grigsby J, Fischer S, Ross S. J Psychopharmacol. 2020 Feb;34(2):155-166. doi: 10.1177/0269881119897615. Epub 2020 Jan 9. PMID: 31916890.

Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, Cameron LP, Patel SD, Hennessey JJ, Saeger HN, McCorvy JD, Gray JA, Tian L, Olson DE. Science. 2023 Feb 17;379(6633):700-706. doi: 10.1126/science.adf0435. Epub 2023 Feb 16. PMID: 36795823.

Psychedelic-inspired drug discovery using an engineered biosensor. Dong C, Ly C, Dunlap LE, Vargas MV, Sun J, Hwang IW, Azinfar A, Oh WC, Wetsel WC, Olson DE, Tian L. Cell. 2021 Apr 8: S0092-8674(21)00374-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.043. Epub 2021 Apr 28. PMID: 33915107.

NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Georgiou P, Fischell J, Elmer GI, Alkondon M, Yuan P, Pribut HJ, Singh NS, Dossou KS, Fang Y, Huang XP, Mayo CL, Wainer IW, Albuquerque EX, Thompson SM, Thomas CJ, Zarate CA Jr, Gould TD. Nature. 2016 May 26;533(7604):481-6. doi: 10.1038/nature17998. Epub 2016 May 4. PMID: 27144355.