You are here

February 23, 2016

Senescent cells tied to health and longevity in mice

At a Glance

- Removing senescent cells—those that had stopped dividing—extended the lifespan of mice and had other health benefits without apparent side effects.

- The results suggest that therapies aimed at removing senescent cells could help counter some effects of aging.

In a process called cell senescence, cells stop dividing to produce new cells. Cells typically become senescent after dividing so many times—or acquiring so many mutations—that they’re in jeopardy of becoming abnormal and potentially dangerous to the organism. Senescence is thus viewed as an anti-cancer mechanism.

Over time, senescent cells accumulate in various tissues and organs. Although no longer dividing, senescent cells are still alive, secreting compounds that may affect the structure and function of the tissues around them. Research suggests that their persistence and accumulation over time can be detrimental to overall health and may play a role in aging.

A research team led by Dr. Jan van Deursen at the Mayo Clinic previously developed a way to remove senescent cells from living mice. Taking advantage of the fact that senescent cells express certain unique genes, they designed transgenic mice in which injection of a drug triggers senescent cells' death. Using this technique, the team found a relationship between senescent cells and certain age-related diseases in a mouse model of premature aging.

In their latest work, the group used the same strategy to investigate the effect of senescent cells on lifespan and health in mice that age normally. The study was supported by NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institute on Aging (NIA), and others. Results appeared on February 11, 2016, in Nature.

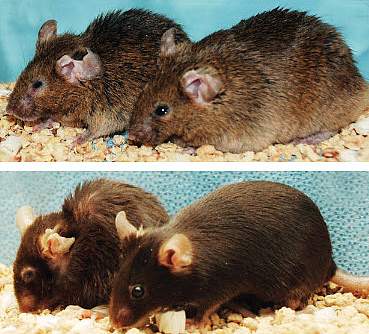

The researchers found that treating mice to remove senescent cells extended their median lifespans by 17% to 42%, depending on sex, diet, and genetic background. The treated mice typically had a healthier appearance than their age-matched controls. Treatment also helped preserve their spontaneous activity and exploratory behaviors.

Significantly, the scientists found that the treatment slowed age-related changes in fat, kidney, and heart functions. It also delayed tumor formation of a variety of cancers, and even delayed cataract formation in one mouse strain.

Tests on the mice showed no differences between treated and untreated mice in motor coordination and balance, memory, exercise ability, or muscle strength. Likewise, metabolic measures such as fasting glucose levels, glucose tolerance, and insulin sensitivity weren’t significantly changed. Further study will be needed to understand precisely how senescent cells exert their effects.

“Cellular senescence is a biological mechanism that functions as an ‘emergency brake’ used by damaged cells to stop dividing,” van Deursen says. “While halting cell division of these cells is important for cancer prevention, it has been theorized that once the ‘emergency brake’ has been pulled, these cells are no longer necessary.”

Researchers are now searching for compounds that can selectively target senescent cells that accumulate with age. Such compounds could be an important step in helping to combat diseases of aging. However, the elimination of senescent cells could have unforeseen consequences in people, and the approach will require close study.

—by Harrison Wein, Ph.D.

Related Links

- Fruit Flies Yield Insights Into Aging

- Epigenetic Clock Marks Age of Human Tissues and Cells

- Aspects of Aging Might Be Reversed

- Removing Nondividing, Senescent Cells in Mice Delays Age-Related Disease

- NIH-Funded Researchers Identify Drugs to Eliminate Senescent Cells in Mice, Improving Health and Function

References: Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, Wijers ME, Sieben CJ, Zhong J, Saltness RA, Jeganathan KB, Verzosa GC, Pezeshki A, Khazaie K, Miller JD, van Deursen JM. Nature. 2016 Feb 11;530(7589):184-9. doi: 10.1038/nature16932. Epub 2016 Feb 3. PMID: 26840489.

Funding: NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institute on Aging (NIA), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); Paul F. Glenn Foundation; Ellison Medical Foundation; Noaber Foundation; Children’s Research Center; and Robert and Arlene Kogod Center on Aging.