You are here

October 1, 2012

Gene Therapy Restores Sense of Smell in Mice

Mice that were unable to smell from birth gained the ability to smell when researchers used gene therapy to regrow structures called cilia on cells that detect odor. The approach might one day lead to treatments for related human genetic disorders.

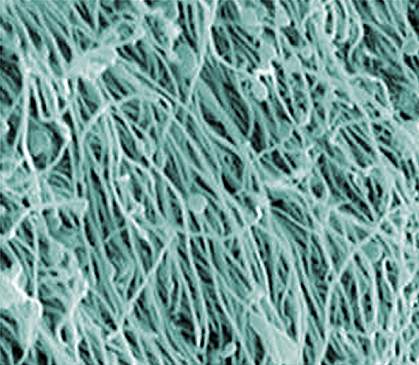

Cilia are antenna-like projections on cells that help them sense their environment. Genetic disorders of the cilia, known as ciliopathies, include diseases as diverse as polycystic kidney disease and retinitis pigmentosa—an inherited, degenerative eye disease that causes severe vision impairment and blindness. In the olfactory system, multiple cilia project from olfactory sensory neurons, cells high up in the nasal cavity. These cilia have receptors on their surfaces that bind odorants. A loss of these cilia results in a loss of the ability to smell, which is called anosmia.

A team of researchers, led by Drs. Jeremy C. McIntyre and Jeffrey R. Martens at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, has been studying mice carrying a mutation in the IFT88 gene. The mutation causes a decrease in the IFT88 protein, which leads to a dramatic reduction in cilia function in several different organ systems, including the olfactory system. To see if the gene might play a role in human disease, the scientists examined the IFT88 genes of over 200 people with severe ciliopathies. Their work was funded by 4 NIH components, led by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communications Disorders (NIDCD).

As reported online on September 2, 2012, in Nature Medicine, the scientists detected IFT88 mutations in several people with severe ciliopathies. Experiments in zebrafish, a common laboratory model for development, confirmed that mutant IFT88 genes can cause developmental defects.

The researchers next used a harmless virus to introduce a healthy copy of IFT88 into the mice with the mutant version. For 3 consecutive days, the mice received intranasal doses of the virus. They were then given 10 days for infected sensory neurons to express the IFT88 protein. After this period, the mice were tested with an odorant called amyl acetate. The researchers found that the mice had regained olfactory function.

In many mammals, including humans, the urge to eat is driven by smell. The mice the scientists studied are born underweight, and their anosmia interferes with their motivation to eat. The body weight of mice treated with the gene therapy was 60% higher than that of untreated mice, showing that restored olfactory function motivated feeding.

This study shows that gene therapy can be used to restore functional cilia in established cells. “These results could lead to one of the first therapeutic options for treating people with congenital anosmia,” says NIDCD Director Dr. James F. Battey, Jr. “They also set the stage for therapeutic approaches to treating diseases that involve cilia dysfunction in other organ systems, many of which can be fatal if left untreated.”

Related Links

References: Nat Med. 2012 Sep 2. doi: 10.1038/nm.2860. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID:22941275.