You are here

August 30, 2022

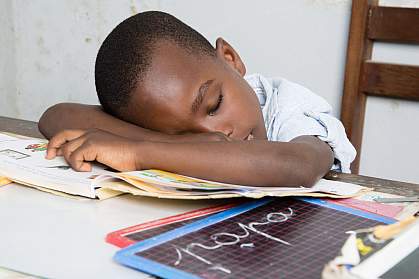

Children’s sleep linked to brain development

At a Glance

- Pre-teens who slept less than nine hours daily had differences in brain structure and more problems with mood and thinking compared to those who got sufficient sleep.

- The findings suggest that sleep interventions might be needed to help improve mental and behavioral health during pre-adolescence and beyond.

Scientists have long recognized that getting enough sleep during childhood can benefit developing brains. However, the underlying brain mechanisms are not well understood. And although experts say that children ages 6 to 12 should get at least nine hours of sleep each day, it’s been unclear how less sleep might affect a child’s brain.

To get some answers, a research team led by Dr. Ze Wang of the University of Maryland set out to see how lack of sleep affects brain structure and other outcomes. They took advantage of data being collected in NIH’s ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. ABCD has enrolled nearly 12,000 volunteers at ages 9 or 10 from research sites across the country. Participants’ health, brain structure and function, and other factors will be followed for a decade as they move from adolescence into young adulthood.

The researchers identified more than 4,000 ABCD participants, ages 9 or 10, who generally got nine or more hours of sleep per day, according to their parents. This group was compared to a similar number of age-matched children who typically got less than the recommended nine hours of sleep. The research team carefully matched the two groups based on some key factors that can confound study results. These factors included sex, household income, body mass index, and puberty status. Participants were assessed and followed over a two-year period. Results appeared in Lancet Child & Adolescent Health on July 29, 2022.

The researchers found that children in the insufficient sleep group at the start of the study had more mental health and behavioral challenges than those who got sufficient sleep. These included impulsivity, stress, depression, anxiety, aggressive behavior, and thinking problems. The children with insufficient sleep also had impaired cognitive functions such as decision making, conflict solving, working memory, and learning. Differences between the groups persisted at the two-year follow-up.

Brain imaging at the start of the study and two years later showed differences in brain structure and function in the insufficient sleep group compared to the sufficient sleep group. The findings suggest that sleep affects learning and behavior through specific brain changes.

“Children who had insufficient sleep—less than nine hours per night—at the beginning of the study had less grey matter or smaller volume in certain areas of the brain responsible for attention, memory, and inhibition control, compared to those with healthy sleep habits,” Wang explains. “These differences persisted after two years, a concerning finding that suggests long-term harm for those who do not get enough sleep.”

Because the ABCD study is ongoing, the researchers note that there will be opportunities to add more follow-up measurements and build on their results. “Additional studies are needed to confirm our findings and to see whether any interventions can improve sleep habits and reverse the neurological deficits,” Wang adds.

—by Vicki Contie

Related Links

- Getting Sufficient Sleep Reduces Calorie Intake

- Lack of Sleep in Middle Age May Increase Dementia Risk

- Poor Sleep Linked with Higher Blood Sugar Levels in African Americans

- Weekend Catch-up Can’t Counter Chronic Sleep Deprivation

- How Night Shifts Disrupt Metabolism

- Sleep Deprivation Increases Alzheimer’s Protein

- Naps Can Help Preschool Children Learn

- Sleep On It

- Good Sleep for Good Health

- ABCD Study

References: Effects of sleep duration on neurocognitive development in early adolescents in the USA: a propensity score matched, longitudinal, observational study. Yang FN, Xie W, Wang Z. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022 Jul 29:S2352-4642(22)00188-2. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00188-2. Online ahead of print. PMID: 35914537.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).