You are here

August 27, 2019

Enterovirus infection linked to acute flaccid myelitis

At a Glance

- Evidence of infection with an enterovirus was found in about 80% of people with acute flaccid myelitis.

- More research is needed to understand whether enterovirus infection contributes to the development of this rare but serious condition.

Since 2014, more than 560 children in the U.S. have been afflicted with a condition called acute flaccid myelitis (AFM). AFM affects the nerves of the body. It can cause sudden muscle weakness and paralysis, usually in the arms or legs. In severe cases, it can interfere with breathing and brain functioning.

Researchers have not yet found the cause of AFM, which makes it difficult to develop prevention and treatment strategies. Many scientists have suspected that infection with a type of virus called an enterovirus plays a role in AFM.

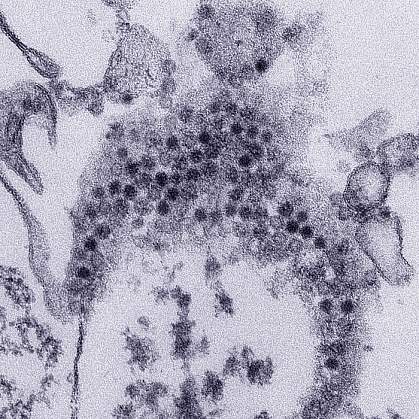

The most notorious enterovirus, which causes polio, has been eradicated in the U.S. through vaccination. But other enteroviruses are still common. They usually have mild effects on the body, such as fever, respiratory symptoms, or stomach upset. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided with outbreaks of the enteroviruses EV-D68 and EV-A71.

Previous studies have looked for enterovirus infection in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of people with AFM, largely without success. However, the techniques used may not have been sensitive enough to pick up traces of enterovirus in the body.

In a new study funded by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), researchers led by Drs. W. Ian Lipkin and Nischay Mishra from Columbia University used advanced technologies to search for enteroviruses.

The team used a sensitive sequencing method called VirCapSeq-VERT to look for viruses in CSF taken from 13 children and one adult with AFM. They also tested blood and CSF samples for antibodies to hundreds of different bacteria and viruses using a new tool called the Serochip. Such antibodies, made by the immune system during an infection, may be found long after the viruses are cleared from the body.

For controls, the researchers also tested 5 children and 11 adults with other diseases of the central nervous system, and 10 children with Kawasaki disease, which doesn’t involve the central nervous system. Results were published on August 13, 2019, in mBio.

Enteroviruses were only detected in one person with AFM and one without. However, antibodies to enteroviruses were found in the CSF of almost 80% of people with AFM. In contrast, they were found in only about 20% of the people with other neurological conditions. No antibodies to enteroviruses were found in children with Kawasaki disease.

The scientists also found that 6 of the 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of the 11 (73%) blood samples from people with AFM had antibodies that reacted specifically to a portion of EV-D68. None of the samples from people without AFM reacted to this region.

None of the people with AFM or other neurological conditions had antibodies to eight tick-borne diseases or West Nile virus in their CSF. Some concerns had previously been raised about these diseases triggering AFM.

While other possible causes of AFM continue to be investigated, this study provides further evidence that enterovirus infection may be a factor in AFM.

“Physicians and scientists have long suspected that enteroviruses…are behind AFM, but there has been little evidence to support this idea,” says Mishra. “Further work is needed with larger, prospective studies; nonetheless, these results take us one step closer to understanding the cause of AFM, and one step closer to developing diagnostic tools and treatments.”

Related Links

References: Antibodies to Enteroviruses in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Acute Flaccid Myelitis. Mishra N, Ng TFF, Marine RL, Jain K, Ng J, Thakkar R, Caciula A, Price A, Garcia JA, Burns JC, Thakur KT, Hetzler KL, Routh JA, Konopka-Anstadt JL, Nix WA, Tokarz R, Briese T, Oberste MS, Lipkin WI. MBio. 2019 Aug 13;10(4). pii: e01903-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01903-19. PMID: 31409689.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).