You are here

December 8, 2014

Gene Therapy Used to Treat Hemophilia

At a Glance

- An experimental gene therapy improved symptoms for as long as 4 years in men with severe hemophilia.

- The study shows the potential for gene therapy as a safe, effective approach for treating this and other genetic disorders.

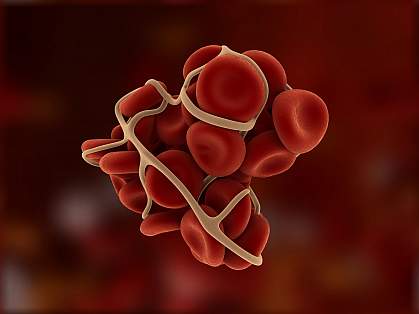

Hemophilia is a rare bleeding disorder in which blood doesn’t clot normally. Hemophilia B is caused by mutations in the gene for coagulation factor IX, a protein that helps blood to clot. People with missing or low levels of factor IX bleed longer than healthy people.

While those with a mild form of the disorder bleed excessively only after injury, about 40-50% of patients have a more severe form that causes spontaneous internal bleeding, which can lead to serious joint damage and even death. The primary treatment for people with severe hemophilia B is injection of factor IX as often as every 3 to 4 days for their entire lives, an often burdensome and expensive therapy.

Researchers from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the University College London, and the Royal Free Hospital have been studying the long-term effectiveness and safety of using gene therapy to treat the disease. The approach takes advantage of viruses that infect humans but don’t cause disease, called vectors. When the human factor IX gene is inserted into these vectors, the viruses deliver the gene into the cells they infect. The cells then manufacture functional protein. Previous studies had some success using such vectors to target the liver cells that produce human factor IX. However, achieving stable long-term expression of factor IX was a challenge, as was a complicating liver toxicity.

For the new study, the researchers inserted the human factor IX gene into an improved vector recently developed for gene therapy called adeno-associated virus serotype 8 (AAV8). Ten men between the ages of 22 and 64 participated in the study. Two were given a low dose of the vector through a peripheral vein, 2 a medium dose, and 6 a high dose. The study was supported in part by NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Results were published on November 20, 2014, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Within 4 months of receiving the modified gene therapy, the patients’ blood levels of factor IX activity increased from less than 1% of normal to between 1% and 6% of normal. Those who received a higher dose of the vector produced higher levels of the clotting protein. Higher doses led to a substantial decrease in bleeding incidents as well as less required treatment with factor IX.

These improvements lasted for the entire monitoring period, which was as long as 4 years for some participants. Side effects were mild. The most common adverse effect, seen in 4 of the 6 men who received a high dose of the virus, was a rise in levels of a liver enzyme—a sign of liver inflammation that was easily treated.

“The results so far have made a profound difference in the lives of study participants by dramatically reducing their risk of bleeding,” says senior author Dr. Andrew Davidoff of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

“The results also provide a solid platform for developing this gene transfer approach for treatment of other disorders,” adds lead author Dr. Amit Nathwani of the University College London.

The clinical trial is ongoing, with discussions currently underway about further expansion to include younger participants.

—by Brandon Levy

Related Links

- Gene Therapy Helps Patients with Hemophilia

- Improving Gene Therapy for Eye Diseases

- What is Hemophilia

- Gene Therapy

- Clinical Trial Information

References: Long-term safety and efficacy of factor IX gene therapy in hemophilia B. Nathwani AC, Reiss UM, Tuddenham EG, Rosales C, Chowdary P, McIntosh J, Della Peruta M, Lheriteau E, Patel N, Raj D, Riddell A, Pie J, Rangarajan S, Bevan D, Recht M, Shen YM, Halka KG, Basner-Tschakarjan E, Mingozzi F, High KA, Allay J, Kay MA, Ng CY, Zhou J, Cancio M, Morton CL, Gray JT, Srivastava D, Nienhuis AW, Davidoff AM. N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 20;371(21):1994-2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407309. PMID: 25409372.

Funding: NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); United Kingdom Medical Research Council; Katharine Dormandy Trust; United Kingdom Department of Health; Royal Free Hospital Charity; Assisi Foundation of Memphis; ALSAC; and Howard Hughes Medical Institute.