You are here

April 2, 2024

Gum disease-related bacteria tied to colorectal cancer

At a Glance

- Scientists identified a specific subtype of bacteria implicated in gum disease that may promote the growth of colorectal tumors.

- The results suggest that therapies targeting these bacteria in tumors could help reduce the severity of some colorectal cancers.

Colorectal cancer—cancer of the colon and rectum—is the fourth most common cancer nationwide. Although overall rates have been steadily falling due to better screening techniques, rates of colorectal cancer in young adults are on the rise. Researchers have been working hard to understand the causes.

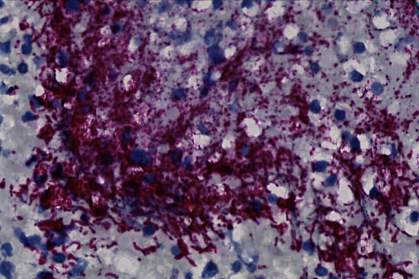

A bacteria implicated in gum disease, Fusobacterium nucleatum, has also been found in some colorectal cancer tumors. F. nucleatum is rarely seen in the guts of healthy people. Colorectal tumors harboring these bacteria are associated with more cancer recurrence and worse patient outcomes than tumors without them. However, it’s unclear how much of a role, if any, the bacteria play in causing the tumors to grow.

F. nucleatum is normally found in low levels in the mouth but can flourish and, along with other microbes, trigger inflammation to cause gum, or periodontal, disease. Over time, this inflammation can lead to destruction of the bone and tissues that support the teeth, resulting in tooth loss. Studies over the years have pointed to a relationship between periodontal disease and other conditions throughout the body, including those of the heart, kidneys, autoimmune diseases, and even some cancers. However, in most cases scientists still don’t entirely understand the degree of involvement, if any, that periodontal disease has in causing these conditions.

An NIH-funded research team led by Drs. Martha Zepeda Rivera, Susan Bullman, and Christopher D. Johnston of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center did a careful genetic comparison between F. nucleatum from colorectal tumors and those from healthy mouths. They analyzed the genomes of 80 F. nucleatum strains from the mouths of people without cancer and 55 strains from tumors of patients with colorectal cancer. The findings were published on March 20, 2024, in Nature.

The team found that one subspecies of F. nucleatum, called Fna, was more likely to be present in colorectal tumors. Further analyses revealed that there were two distinct types of Fna. Both were present in mouths, but only one type, called Fna C2, was associated with colorectal cancer.

When the researchers infected mice that had inflamed intestines (an animal model of colitis) with these two types of F. nucleatum, they found that mice infected with Fna C2 developed more tumors than those infected with the other type.

It’s not quite known yet how these bacteria travel from the mouth to the colon. However, the researchers showed that Fna C2 could survive longer in acidic conditions, like those found in the gut, than the other type of Fna. This suggests that the bacteria may travel along a direct route through the digestive tract.

“We have pinpointed the exact bacterial lineage that is associated with colorectal cancer,” Johnston says, “and that knowledge is critical for developing effective preventive and treatment methods.”

Future studies can test if specifically targeting F. nucleatum in colorectal tumors can improve patient outcomes. Clinicians might also one day be able to screen for Fna C2 to identify colorectal tumors that are more likely to be aggressive.

—by Vanessa McMains, Ph.D.

Related Links

- Anti-Diabetes Drugs May Reduce the Risk of Colorectal Cancer

- Y Chromosome Affects Cancer Growth

- Vaping Alters Mouth Microbes

- Mouth Microbes: The Helpful and the Harmful

- Your Body’s Bugs: Nurturing Healthy Microbes

- Colorectal Cancer

References: A distinct Fusobacterium nucleatum clade dominates the colorectal cancer niche. Zepeda-Rivera M, Minot SS, Bouzek H, Wu H, Blanco-Míguez A, Manghi P, Jones DS, LaCourse KD, Wu Y, McMahon EF, Park SN, Lim YK, Kempchinsky AG, Willis AD, Cotton SL, Yost SC, Sicinska E, Kook JK, Dewhirst FE, Segata N, Bullman S, Johnston CD. Nature. 2024 Mar 20. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07182-w. Online ahead of print. PMID: 38509359.

Funding: NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), and Office of the Director (OD); W.M. Keck Research Foundation; Washington Research Foundation; Bio & Medical Technology Development Program, Korea.