You are here

November 25, 2013

Key HIV Protein Structure Revealed

Researchers have developed a more detailed picture of the protein largely responsible for enabling HIV to enter human immune cells and cause infection. The findings help reveal how HIV gains entry into cells and will inform future strategies to combat the virus.

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, infects more than 34 million people worldwide. Once in the body, HIV attacks and destroys immune cells. Current treatment with antiretroviral therapy helps to prevent the virus from multiplying, thus protecting the immune system. Despite recent advances in treatment, scientists haven’t yet designed a vaccine that protects people from HIV.

The viral surface protein known as Env is a major target for potential HIV vaccines. One challenge in developing a vaccine is that Env can mutate rapidly. These changes to the protein’s surface help it to evade the immune system. The surface of the Env protein is also protected by a coat of sugar molecules that helps shield it from the immune system.

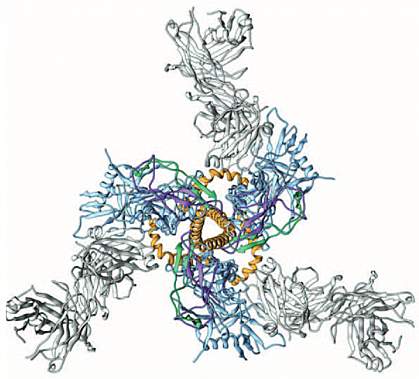

Env extends from the surface of the HIV virus particle. The spike-shaped protein is “trimeric” — with 3 identical molecules, each with a cap-like region called glycoprotein 120 (gp120) and a stem called glycoprotein 41 (gp41) that anchors Env in the viral membrane. Only the functional portions of Env remain constant, but these are generally hidden from the immune system by the molecule’s structure.

X-ray analyses and low-resolution electron microscopy have revealed the overall architecture and some critical features of Env. But higher resolution imaging of the overall protein structure has been elusive because of its complex, delicate structure. Three new papers use stabilized forms of Env to gain a clearer picture of the intact trimer.

An NCI research team led by Dr. Sriram Subramaniam used cryo-electron microscopy to examine the Env structure. The study appeared on October 23, 2013, in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology.

Scientists at the Scripps Research Institute and Weill Cornell Medical College used both cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography to examine Env. Their work was supported in part by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), and National Cancer Institute (NCI). Results were published in 2 papers online on October 31, 2013, in Science.

The studies revealed the spatial arrangement of the Env components and their assembly. They determined the relationships of the gp120 and gp41 subunits and provided information about the interaction of Env with neutralizing antibodies, which can block many strains of HIV from infecting human cells.

“Most of the prior structural studies of this envelope complex focused on individual subunits, but the structure of the intact trimeric complex was required to fully define the sites of vulnerability that could be targeted, for example with a vaccine,” says Scripps researcher Dr. Ian A. Wilson, a senior author of the Science papers.

“Now we all need to harness this new knowledge to design and test next-generation trimers and see if we can induce the broadly active neutralizing antibodies that an effective vaccine is going to need,” adds Weill Cornell scientist Dr. John P. Moore, another senior author of the research.

— by Harrison Wein, Ph.D.

Related Links

References: Prefusion structure of trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein determined by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013 Oct 23. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2711. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 24154805. Cryo-EM Structure of a Fully Glycosylated Soluble Cleaved HIV-1 Envelope Trimer. Science. 2013 Oct 31. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 24179160. Crystal Structure of a Soluble Cleaved HIV-1 Envelope Trimer. Science. 2013 Oct 31. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 24179159.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and National Center for Research Resources (NCRR); the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE); the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research; the European Research Council; the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; the National Research Council Canada; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; the Province of Saskatchewan; Western Economic Diversification Canada; the University of Saskatchewan and the Ragon Institute.