You are here

May 24, 2010

Sickle Cell Disease May Affect Brain Function

Adults who have mild sickle cell disease scored lower than healthy participants on tests of brain function, suggesting that the blood disease may affect the brain more than previously realized. The new study is the first to examine cognitive functioning in adults with sickle cell disease.

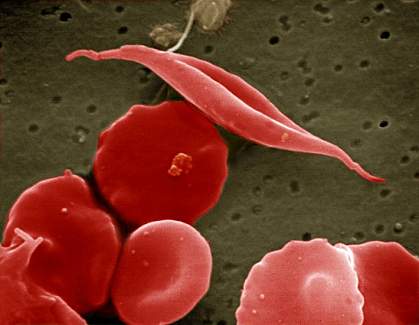

Sickle cell disease affects about 70,000 Americans, mostly those of African descent. The condition arises from an altered gene that produces abnormal hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is a protein that helps red blood cells carry oxygen throughout the body. The faulty hemoglobin can lead to distorted red blood cells, which become crescent-shaped, stiff and sticky. These sickle-shaped cells can clump together to block blood flow, causing severe pain and potential organ damage. Because they don't last as long as normal, round red blood cells, the sickled cells can lead to anemia.

Only a few decades ago, many patients with sickle cell disease died during childhood. But with improved treatments, more patients are living into middle age. Health care providers are now uncovering previously unrecognized complications, including potential defects in thinking and brain function.

To take a closer look, a multi-center research team led by Dr. Elliott P. Vichinsky of the Children’s Hospital and Research Center in Oakland, California, tested cognitive functioning in 149 patients, ages 19 to 55, with sickle cell disease. All were considered at low risk for complications from the disease because they had no history of frequent pain episodes or hospitalizations, stroke, high blood pressure or other conditions that might affect brain function. For comparison, the scientists also evaluated 47 healthy people of similar ages and education levels from the same communities. The study was funded by NIH’s National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

In the May 12, 2010, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, the scientists reported that brain function scores in sickle cell patients were, on average, in the normal range. However, more patients with sickle cell disease scored lower on measures such as intellectual ability, processing speed and attention compared to people in the healthy group. Those with the lowest scores were older and had the lowest levels of hemoglobin. Findings from brain MRI scans did not explain the differences in scores.

Because the scientists didn’t compare the sickle cell patients to otherwise healthy patients with anemia from other causes, it’s not clear if the cognitive defects are linked to the sickle cell condition itself or to the resulting anemia, which might reduce oxygen delivery to the brain. The researchers note that previous studies have linked anemia to poorer neurocognitive performance, and that test results can improve by boosting hemoglobin levels. The scientists have launched a clinical trial to see if blood transfusions might help preserve cognitive function in sickle cell patients.

"We need to study whether existing therapies, such as blood transfusions, can help maintain brain function, or perhaps even reverse any loss of function," says Vichinsky. "These effects were found in patients who have clinically mild sickle cell disease, which raises the question of whether therapies should be given to all patients to help prevent these problems from developing."