You are here

October 27, 2020

Study sheds light on key steps in the HIV life cycle

At a Glance

- Researchers were able to uncover key steps in HIV replication by reconstituting and watching these events unfold outside the cell.

- The system created by the scientists may be useful for future studies of these early stages in the HIV life cycle.

HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus, is the virus that causes AIDS—acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. More than a million people in the United States are living with HIV today. HIV attacks the immune system by destroying immune cells vital for fighting infection. Without treatment, the virus gradually destroys the immune system and cause AIDS.

Scientific advances have changed HIV from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic condition. Researchers have developed drugs that allow people with HIV to lead long, heathy lives. These medications, called antiretroviral therapy, also help prevent the spread of HIV to others. But while many advances have been made, there is no cure for AIDS. Scientists are still working to learn more about the basic biology of HIV.

Researchers led by Dr. Wesley Sundquist of the University of Utah Health and Dr. Owen Pornillos of the University of Virginia set out to better understand key steps in HIV replication. To infect a cell, the membrane that encloses HIV first fuses with the surface of the host cell. This brings the cone-shaped capsid containing the virus’s genome and replication enzymes into the cell.

Once inside the cell, the virus’ genetic material―single-stranded RNA―gets converted by an enzyme called reverse transcriptase into the double-stranded DNA that humans use to store our genetic code. This DNA is then integrated into the cell’s DNA by an enzyme called integrase.

Scientists have debated the role of the HIV capsid. It was unclear whether reverse transcription could take place inside the capsid and whether an intact capsid might promote the process. The new study gives insight into these questions. It was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Results were published in Science on October 9, 2020.

The researchers were able to create conditions in the lab where they could watch reverse transcription and integration unfold. They could manipulate the capsid and observe its effects on HIV replication.

The team found that reverse transcription depended on the capsid’s structure. When they used genetic and biochemical methods to destabilize the capsid, reverse transcription couldn’t efficiently convert HIV RNA into DNA.

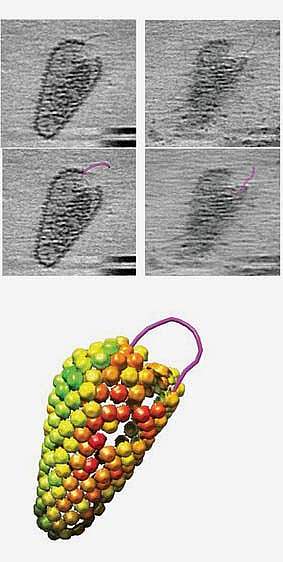

They were able to confirm this visually using cryo-electron microscopy and molecular modeling. The imaging revealed that most capsids remained intact or nearly so during DNA synthesis. This suggests that reverse transcription must take place inside a largely intact capsid.

The scientists also discovered that disassembling the capsid, known as uncoating, may be necessary for integration to occur. They integrated the newly formed HIV DNA into a circular DNA molecule, similar to the process in cells. To do so required added extracts from human cells. Further study will be needed to determine which cell components are critical for integration.

“Our findings reveal essential insights into reverse transcription and integration of the HIV genome,” Sundquist says. “We anticipate that our cell-free system will help advance future studies of the early viral life cycle.”

Related Links

- New Strategies Drive HIV from Cellular Hiding Places

- Antibody Combination Suppresses HIV

- Benefits of Early Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV Infection

- Compound May Protect Against HIV.

- HIV Vaccine Progress in Animal Studies

- Key HIV Protein Structure Revealed

- HIV/AIDS

- HIV

References: Reconstitution and visualization of HIV-1 capsid-dependent replication and integration in vitro. Christensen DE, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Johnson JS, Pornillos O, Sundquist WI. Science. 2020 Oct 9;370(6513):eabc8420. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8420. PMID: 33033190.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); University of Virginia School of Medicine.