You are here

Advances in HIV/AIDS Research

Search for HIV Vaccine Gets a Shot in the Arm

Scientists have been striving for a safe and effective vaccine to prevent HIV infection ever since the virus was identified in 1984. The first signal that such a vaccine is possible came in September 2009 from a clinical trial funded in large part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). With more than 16,000 adult participants in Thailand, the trial showed that an investigational vaccine regimen was safe and 31 percent effective at preventing HIV infection.

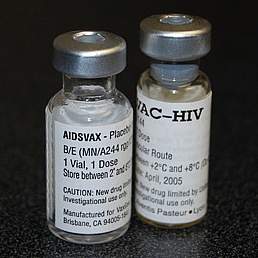

The vaccine regimen consisted of two separate vaccines. The first was a killed canarypox virus containing pieces of HIV DNA, and the second was an HIV surface protein that plays a key role in infection. This regimen was based on HIV strains that commonly circulate in Thailand. The main goal of the vaccine regimen was to train the immune system to attack HIV, so that if a vaccinated individual were exposed to the virus, his or her immune system would successfully fight off the infection. A secondary goal was to determine if the vaccine regimen could reduce the amount of HIV in the blood of vaccinated study participants who later became infected with the virus.

Conducted in the Rayong and Chon Buri provinces of Thailand, the trial enrolled more than 16,000 men and women ages 18 to 30 years old at various levels of risk for HIV infection. Participants received either the vaccine regimen or a placebo and were tested for HIV infection every 6 months for 3 years. During each clinic visit, the participants were counseled on how to avoid becoming infected with HIV.

Led by the Thai Ministry of Public Health’s Department of Disease Control, the study was sponsored by the U.S. Army in collaboration with NIAID, Sanofi Pasteur and Global Solutions for Infectious Diseases.

In the final analysis, 74 of 8,198 placebo recipients became infected with HIV compared with 51 of 8,197 participants who received the vaccine regimen. This difference in the number of people who became infected was statistically significant, meaning it is unlikely the study results were due to chance. The vaccine regimen did not reduce the amount of virus in the blood of people who became infected with HIV.

NIAID and its partners in this study are now working with other scientific experts to understand how the vaccine regimen in the Thai trial protected some participants from HIV infection, with the hope of using that knowledge to create a more effective HIV vaccine.

To learn more about this study and NIAID’s HIV/AIDS research, go to https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/hivaids.

This page last reviewed on October 1, 2024